Tsunamis and The Big One: A Tofino History Lesson

Less than a month ago—on December 24th, 2019—Mother Nature and Poseidon celebrated an early Christmas together, making the Earth shake in the waters underneath the waters just off Vancouver Island, 182 kilometers (113 miles) west of Port Hardy. Heeding warnings from the United States Geological Survey, coastal residents braced for disaster, finding high ground as soon as possible. As a child growing up in Port Hardy, I recall a similar warning, but I don’t remember such wise action. Instead of moving uphill, we—along with hundreds of other Port Hardy residents—sauntered down to the shoreline to “watch the tidal wave.” It was idiotic.

On October 22, 1960, a magnitude 9.5 earthquake off the coast of Chile took a whole lot of water on a long-distance vacation all the way to Tofino, where it arrived as a 1.2-metre wave. It reportedly caused headaches all the way up the coast of Vancouver Island and crushed logging booms in Haida Gwaii, and obliterated large parts of the Hawaiian town of Hilo. Tofino faired ok.

Fortunately, none of these energetic aquatic threats caused true destruction near Tofino, but the mere mention of them makes B.C. residents remember a tsunami that did. On Good Friday, March 27, 1964, the fiercest North American earthquake of the century hit Anchorage, Alaska. Some reports claim it was 8.5 magnitude. Others 9.2. Whatever it registered, it did serious damage, shifting the infamous Cascadian Subduction zone plates and altering the landscape of the coast for decades. It also shifted our fear of tsunamis permanently. What happened next would go down in history. The quake sent a tsunami hurtling toward B.C.’s south coast at 700 kilometres an hour. When it made landfall, it measured at 4.3 metres. That’s 14 feet of badass destruction moving with a velocity capable of moving homes, cars and even commercial buildings. And that’s exactly what it did in Port Alberni.

While houses in Hot Springs Cove and Bamfield both were affected with basements flooded and shaken foundations, it was the fjord-like high mountain sides of Alberni Inlet that would take it the worst. The massive surge of ocean energy funneled into the Inlet, choked up into an even higher and more devastating wall of water (some reports say 21 feet), and tossed Port Alberni’s salad. Thankfully, no one died, but it did $8 million dollars in damage, which accounts for whopping $65 million in 2019 bucks.

Earthquakes and tsunamis are a fact of life on the coast, as evident by mythical and historical accounts by First Nations, and the deafening tsunami sirens installed at Chesterman Beach and Cox Bay in 2017. The scars of the more massive tsunamis can still be seen on mountainsides and beaches up and down the west coast. These are dubbed “ghost forests,” cedar and fir trees killed by saltwater that created a literal high water mark. Carbon dating of some ghost forests confirms these events happened some time between 1680 and 1720.

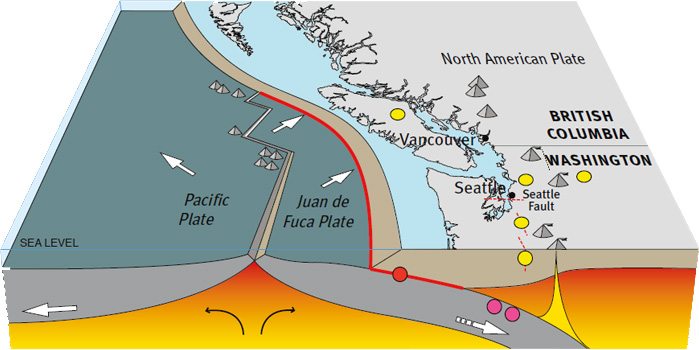

Indeed, long before Europeans could catch a Coho, the Cascadian Subduction Zone has terrified what is now known as the Pacific Northwest. And six earthquakes of magnitude 9.0—or more—have gone down and over the past century. And they all revolve around the Cascadian Fault. Stretching from northern Vancouver Island to northern California, the Cascadian Fault clumsily bisects the Pacific Plate and the Juan de Fuca Plate. Both of these chunks of earth’s crust are beneath the continental crust. An excellent, comprehensive and terrifying feature story in Coast Mountain Culture magazine by writer Allie Jenkinson explains: “The former is a thinner oceanic plate that is slipping below the offshore crust of the Pacific Northwest as the North American plate moves in a general southwest direction. As the oceanic plate slips further underneath, its temperature increases until it is no longer able to store mechanical stress, releasing the energy as the plates inevitably slip, resulting in what is known as a “megathrust” earthquake, the name given to seismic activity that occurs at the convergence of multiple plates. This type of earthquake is the most powerful…” Experts say it’s not a question of if…but when. Well, shit.

So, what do we need to know here in Tofino? A “megathrust” earthquake will cause ground shaking that lasts three to five minutes, the kind that will literally knock you on your ass. At this point, do not wait for someone to tell you to move. Official notices for evacuation will come, but you should get going right away. That wave is probably coming whether Twitter tells you or not. Run, don’t walk, to as high as ground as possible…10 metres above high tide line at the very least. A tsunami is not one wave, but a series of waves growing and then diminishing over a period of about 12 hours, so bring supplies if you can. Have a bag ready to rock at all times. Overall, remember, that Tofino is far from the only place that deals with this threat. From Alaska to California, we all live and play in the shadow of tsunamis. Don’t live in fear. Just be prepared, eh.

For Tofino locals:

· Sign up for Tofino’s One Call Notification system.

· Have a grab-and-go emergency kit (a “bug out bag”) as well as at least one-week’s supply of food

· Know where to bounce to. Look at this evacuation map now…not then.

· Do not return to low-lying areas to gather belongings after waves recede. Emergency officials will let you know when it is safe

Want to read more? Click here to go back to our blog.