Feb 13, 2026

A Couple’s Guide to Tofino

Here’s our version of romance, Tofino-style. Tofino isn’t your average couples getaway. It’s not rose petals on the bed and matching white robes (though we’ve got those too,…

Feb 05, 2026

How Tofino Came to Be: A Living History

Wind, water, and ancient forests shape this place, but so do the people who have called it home for thousands of years. Long before surfboards, wooden boardwalks, or busy summers, Načiks (Tofino) has…

Jan 06, 2026

The Cold-Water Boost: What Happens to Your Body During a Winter Ocean Dip

There’s something a little wild (some would say, unhinged) about wading into the Pacific in the middle of winter. Maybe it’s the adrenaline, maybe it’s the thrill, or maybe it’s the fact that it instantly wakes up every…

Dec 09, 2025

Pacific Rim Whale Festival: March 14–21, 2026

Every March, the coastline of Vancouver Island becomes a front-row seat to one of the greatest wildlife journeys on Earth. The Pacific Rim Whale Festival returns once again with an…

Dec 02, 2025

Why Evergreen Trees Feel So Timeless in the Holiday Season

There’s a certain comfort to walking through Tofino in December and realizing the forest hasn’t changed its outfit at all. While most of Canada sheds its leaves and settles into winter, our…

Nov 13, 2025

Your Guide to Winter in Tofino: Taking Advantage of The Cozy Season

You know it’s winter in Tofino when the crowds dwindle and the mist and rain roll in. The town’s rhythm slows, and while it may feel darker, quieter, and,…

Nov 04, 2025

Tofino’s Ocean Oddities: Strange Things the Storms Wash Ashore

When the Pacific throws a tantrum in the fall and winter, Tofino’s beaches become a kind of natural treasure hunt. Storms don’t only rearrange sand, they deliver objects with stories:…

Nov 02, 2025

Sea of Lights: December 2026

Thank you to all who joined us for the 6th annual Sea of Lights, a beloved tradition at Tofino Resort + Marina where locals and visitors gather to toast…

Oct 07, 2025

The Science of Storms: Why Tofino is Canada’s Storm Watching Capital

When you hear people talk about storm watching in Tofino, it might sound like nothing more than a cozy excuse to sip tea while waves crash outside your window.

Sep 16, 2025

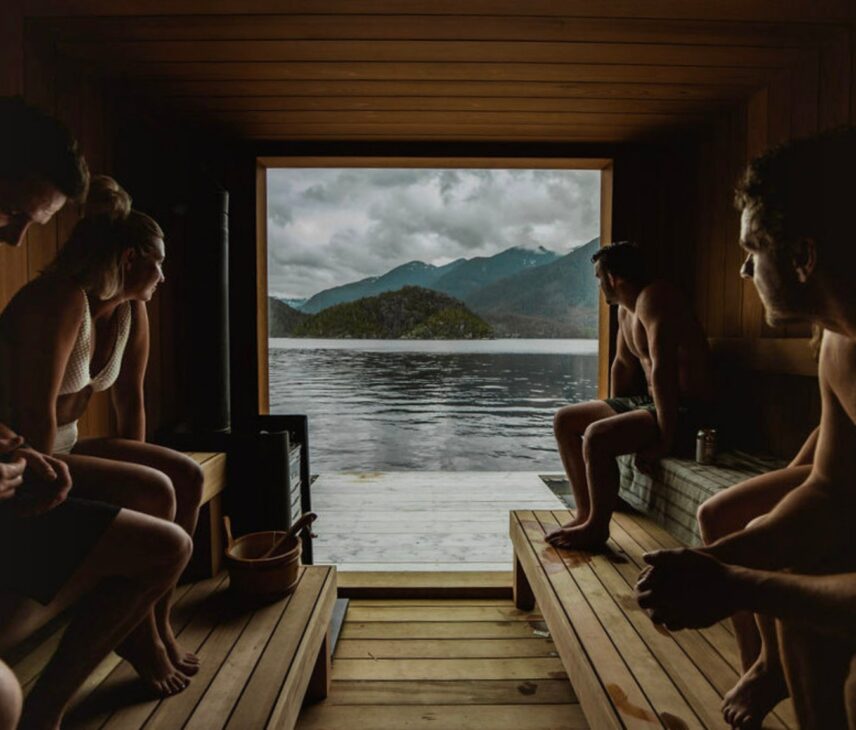

Introducing the Community Floating Sauna Experience for Tofino and Ucluelet Locals

Our Remote Floating Sauna has become one of the most sought-after wellness escapes in Tofino, and for good reason. Set deep within a UNESCO Biosphere Reserve on the traditional…